Selfoss Logbook: Anneli Skaar & Jonathan Laurence

Day 1 : Cokes and Smokes

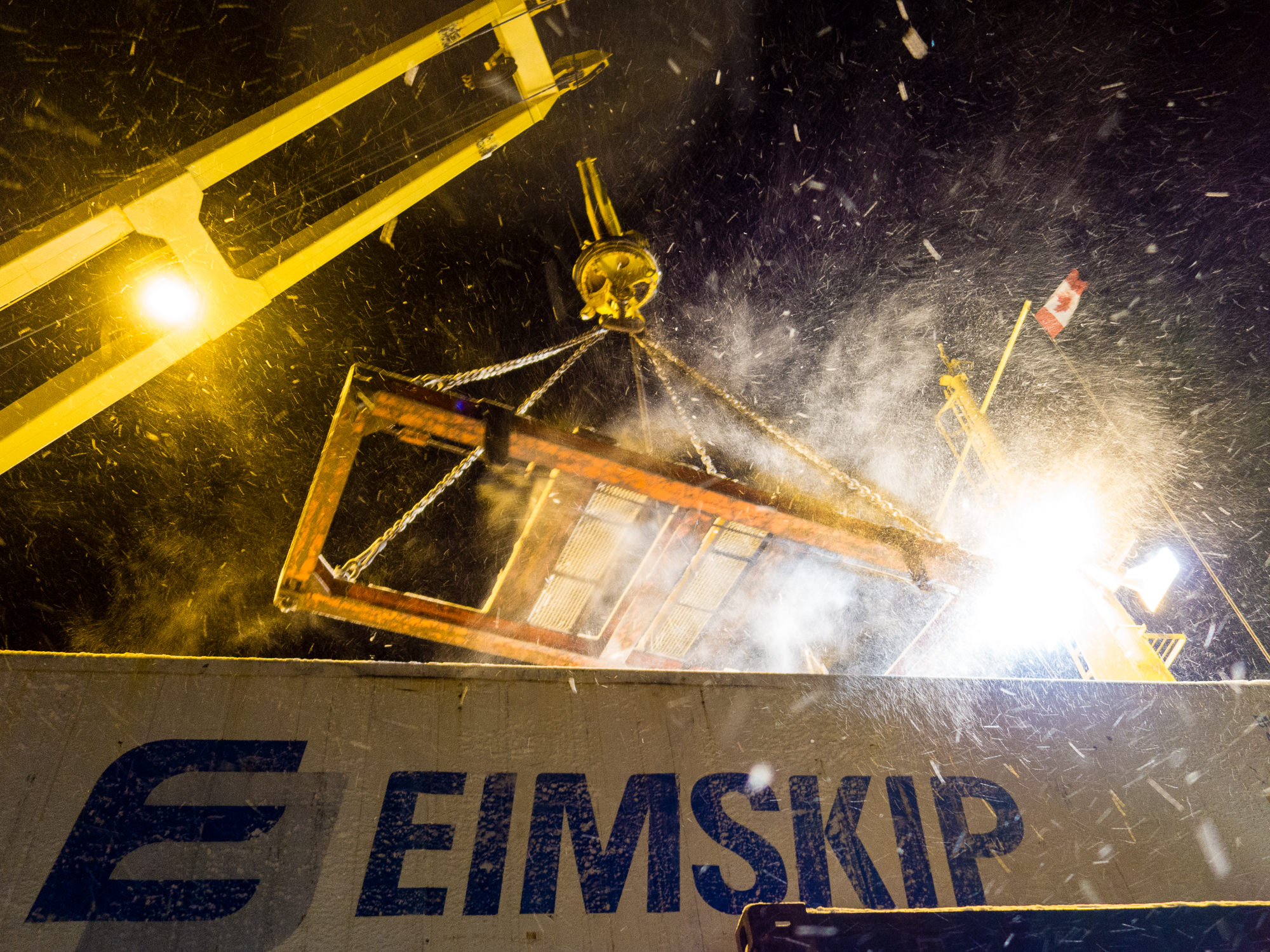

Our departure has been delayed. This fact is not particularly surprising if you take into consideration where our 400 foot ship has come from; Iceland, by way of the harsh North Atlantic. The ship was slammed for the past week with hurricane force winds, waves as high as seven or eight story buildings, and frozen seaspray. Finally in Portland, all the ship’s containers are carefully unloaded, and Selfoss is once again being fitted for the return trip with many 40 foot long blocks. It’s a beautifully choreographed dance of lifts and trailers that would make any little kid ditch their Legos.

It’s on this day that Jonathan and I are allowed to finally come on board after months of anticipating this residency. Marisa, Jonathan’s girlfriend, has driven us down from the midcoast and walks us up the steep gang plank. It’s still a day early, however — we wont depart until tomorrow. EIMSKIP’s management is simply making sure that their guests get settled in well in advance of the increasingly fluid departure time. This departure time is informed by the incoming snow storm and reevaluated on an hour-to-hour basis. For Jonathan and myself, we just want to make sure that the crew of Selfoss doesn’t leave without us. Safely dug in on board, with passports handed over, we ask our Captain whether or not he would leave us if we didn’t arrive promptly.

“Of course,” Captain Kalli says, “YOU we would leave behind. But we would not leave without the cook.”

Captain Kalli is Karl Gudmundsson, the charismatic and personable captain for Eimskip’s GREEN LINE, which has a route of Portland > Newfoundland > Iceland > England > Netherlands only to turn around and go back the way it came. It’s a job with 5 weeks on and 5 weeks off, and Kalli has done this particular route for a year and a half, although he has worked for Eimskip for 37 years. This line has only included Portland since 2013 when the Icelandic shipping company Eimskip struck a deal to have this Maine port be the location for their East Coast hub.

Captain Kalli is the first crew-member we meet when we come onboard on deck A this evening, and rather than a Captain Nemo or a Captain Hook, we find ourselves with an Icelander with a very dry wit, a blondish grey six o’clock shadow, an unruly hipster haircut, and a penchant for Coca Cola and cigarettes. Kalli has kind eyes and an easy smile, but you can also tell that although he is good-humored and friendly, he doesn’t fuck around when it comes to the safety for his 12 person crew.

He meets us barefoot, wearing two very colorful and patterned unmatched socks. Upon our questioning him about this unusual choice of footwear, he tells us he has another pair just like them, only for the reverse feet. Kalli is also holding a can of Coca Cola, one of many we will see him nursing during the time on board.

“One thing we will never run out of onboard,” he assures us, pointing at his red Coca Cola can as we enter the mess room on deck B, “are Cokes and smokes.” He shows us briefly around the small mess room. “This is where you come down for breakfast at 8:00.”

“So deck B is for Breakfast?” I joke. He nods.

“The smoking room is also here, next door.” He adds, pointing to a small room down the hallway. Jonathan perks up at this.

We’re given a casual tour of the rest of the main rooms, and Kalli helps carry my bag up the 6 flights of steep, narrow steps to deck F, just underneath the bridge on deck G. Jonathan and I are both giddy about finally leaving but also excited about the relatively spacious bunk cabin we’ve been alotted. The room, marked with an ironic little sticker that says Hotel Selfoss, has 2 bunkbeds, a desk, and an en suite bathroom with shower.

“Thank you. We’re really looking forward to this crossing,” Jonathan tells Captain Kalli as the Icelander heads for the bridge.

“Looking forward to it? OK, if you say so,” says Kalli.

We slowly realize that everything in our cabin is either connected to something else with a bungee cord, connected permanently to the metal wall with bolts or magnets, or tucked under the bed and sofa. Kalli’s statement is pregnant with the unspoken assumption that we are going to start barfing our brains as soon as we are out on the stormy North Atlantic. We will likely be departing the next day at 2 or 4 pm.

We say goodbye to Marisa who heads back up north, but not before she takes a photo of us from shore. As we settle in for the evening, arranging our photography gear, easels, ginger pills, saltine crackers, tripods and scopolamine patches which will need to last us for the whole trip, we note that the green rubber mats on all flat surfaces will keep everything from violently sliding around.

We decide that deck F stands for, “Oh, fuck”.

Day 2 : Balls Redux

Today’s the day! We are informed that we will be leaving Portland at noon. Or 2pm. Or perhaps later. We are definitely leaving at some point today, guaranteed.

The crew and management is still watching the storm and securing our cargo on deck, but they do need to head out soon as not to delay the whole line any more than they have to.

Jonathan and I start our day in the mess room where coffee and a huge spread of a smørgåsbord has been set up. Out the window we see containers continuing to be lowered onto the deck. We have fresh baked bread, cold cuts, sliced eggs, pickled herring, and slabs of cheeses prepared by our imposing cook, Hannes, as well as about 8 different kinds of milks with Icelandic labels.

Contrary to what people might think, my fluent Norwegian is completely useless in the event having to understand, read, or speak Icelandic. Danish and Swedish are about as different from Norwegian as Irish or Scottish is to American English, so that’s no problem. However, Icelandic is the language of the Vikings and although arguably somewhat changed from that time, it is essentially as close as you’re going to get to old Norse today. But what not everyone realizes is that although it is an ancient sibling of modern Norwegian, my Norwegian is more related to Danish, and I can only understand about 5% of what’s going on here.

For all intents and purposes this means that I have just enough understanding that I can listen to the Viking banter and not assume that they are plotting to kill Jonathan or myself by axing us in our sleep or lobbing us overboard as shark bait. They are actually talking about how to get the Norwegian and American guests to not pour sour cream into their coffee.

The walls of the mess room have several pieces of art, and surely they are loaners from Eimskip’s vast collection of artwork collected over the duration of 100 years of artist residencies on board their ships. They have done several such residences more recently over the last few years with writers, photographers, and visual artists. Further back in the past century, this was a way to give free passage to artists wanting to travel overseas at a time when travel by ship was still more common than by air. Eimskip’s headquarters in Reykjavik is packed wall to wall with original artwork. They still have much more in storage, and they circulate the artwork regularly.

There is a faded sepia-toned photograph of a jackal bolted to the wall in the mess room. Naturally, we ask what the significance is of this. No-one seems to know how the jackal got there, perhaps it is leftover from the previous shipping company that owned this vessel.

“We don’t really know the story about it,” Kalli says, “But it would be bad luck to take it down. So we leave it there.”

We spend the rest of our day at dock familiarizing ourselves with the ship, checking our watches and waiting, and doing an interview with channel 6 as well as getting a photo-op with Congresswoman Chellie Pingree. Somewhere along this course of events we are told that today is Icelandic Balls Day.

After ensuring that we have heard this correctly, Jonathan and I can not believe our luck. We extract that Balls Day means meat balls for lunch, perhaps some fish balls for dinner, and there are whisperings about some sort of cream ball pastry for afternoon coffee. And sure enough, there are the best lamb meat balls I’ve ever had, served for lunch in the ship. They are so good, in fact, that we go for a second “Lance Armstrong” helping of an extra single ball. It is confirmed that cocoa with cream puff balls will be served at 15:00. We now understand why no-one will leave shore without the cook.

Departure has been confirmed for 18:00. The snow storm has started in earnest, and we are invited up to the bridge to watch as our pilot leads us out into the Bay of Maine.

Slowly pushing out from the dock, the quiet rumble of the ship can be felt right down to our bones like a good bass. We try to stay out of the way as the Captain, Chief Officer and pilot negotiate our way out of the harbor. Through the 360 degree view out the bridge’s windows, snow is coming down hard and the pilot ship goes ahead to lead us with its bright red lights in the pitch black darkness. As soon as we are out on course and clear of anything in the inner harbor, the pilot boat zips back to us, lies up against our starboard side at the exact same speed of 8 knots.

It’s time to go. His job done on board, the pilot shakes the captain’s hand and he literally hops out onto the icy deck and climbs down the slippery 7 levels of the outside of the ship to disappear into the darkness in nothing but a dress shirt and an orange vest, whipped by the snow and ice coming in sideways. Two minutes later we spot him, scurrying down a rope ladder above the glowing waves of the massive ship, lit by a spotlight. Jonathan and I think the same thing: that guy has some huge fucking balls. He jumps nimbly into the waiting pilot boat which makes a big arch to return to Portland. His last message to us comes across the radio.

“Selfoss, we are getting out of your way. Have a safe voyage.”

The choppy seas begin in earnest as we clear the port and head to open water. At 19:00 we head down to the mess room where dinner is being served. On the menu is smoked, salted lamb which has clearly been hacked into bits by some sort of Viking hammer that Hannes keeps in the galley for just such occasions.

“But where are the balls? It’s balls day!” I’m already starting to feel some queasiness as the mess room sways from side to side, but I’m trying to ignore it by making small talk.

“Oh yes, there are balls. Didn’t you get some?” Captain Kalli, who has left the ship’s control in the capable hands of the chief officer, goes back to the buffet and returns with a slab of aspic which appears to contain tiny white spheres the size of olives.

“This is, how do you say … lamb testicles.” At this point everyone in the galley has turned around to look at us. The room is silent except for AC/DC playing on the radio. Jonathan and I look at each other. We take a bite. When in Rome, as they say.

“Where are your balls?” I ask, chewing the somewhat gummy texture in the sour jellied aspic, looking at the crew’s plates. It appears that no one is eating the lamb testicles except us.

“We don’t eat those. They taste terrible,” someone chimes up. The captain hands me a can of Coke. Clearly we are being tested. Or testicled, as it were.

I’ll spare you the details, but before bedtime I will see all of todays balls again during the course of three visits to the head. And I was really hoping not to get sick. Oh well.

Balls.

Day 5 : Amuse-Bouche

We left Newfoundland last night after 12 hours loading, unloading, and fueling up before our ocean crossing. It took us about 3 days to get there from Portland, Maine.

I had really big plans to write an entry every day, but have now realized I will just have to write when I have the opportunity. Mainly because I can no longer remember what day it is, and just to further mess with us they keep pushing the clock forward a half or whole hour every day.

Argentia, Newfoundland is a small Canadian port out in nowhere, far east at the edge of the ocean. We woke up yesterday morning to see a landscape out our window that was reminiscent of Lofoten, Norway, with its dramatic and exaggerated mountains. There were people on small skiffs cruising the bay shooting puffins with rifles before scooping them into nets. FYI: Up here, guns don’t kill puffins — men and women in black ski masks kill puffins. The port was literally a concrete dock with a few small buildings and pretty much nothing else. No stores, no restaurants, no shops — it is about as functional as it gets. So much for tax free shopping — not that we need anything.

Since we started on this trip, Jonathan and I have been literally and figuratively stunned by the amount of hearty food we’ve been served. Not just some Cheerios from a box, either — serious, home-cooked, no-bullshit hot meals at 8:00, 12:00, 18:00 — and for good measure there is some sort of baked pastries and coffee at 15:00 just in case the other three meals aren’t enough to give you cardiac arrest. If you have a problem with gluten, meat, or sugar — this trip is decidedly not for you.

Yesterday everyone had their hot breakfast as usual and suited up to go out and do their respective jobs. This was really the first time we had an opportunity to see the crew in action as they secured Selfoss to the shore and started a long, hard day juggling massive containers on and off the ship, in a snow shower no less. One thing is increasingly apparent: this is no work for chickens. The alcohol ban onboard makes a lot more sense when you understand what a detail oriented job this is. Mistakes can result in huge losses, not only in profit but in lives. Precision and safety are everything.

Knowing this, our meals make more sense as well. Hearty traditional food for hard work — but it also it means important downtime for the crew. Something steady, dependable and enjoyable. A family meal of sorts where everyone gathers for their food. And arguably a nice reward for not dropping a container on someone.

The food is the social connection, along with hanging out in the smoking room. Kalli tells me that the “smoking room” is a newer concept, that smoking used to be an important social connection between all the crew onboard, a common pastime that has been somewhat toned down by the designation of a specific area for this activity.

“I guess I need to start smoking,” I tell Kalli. I’ve probably smoked a half a pack since the beginning of the trip in second hand smoke alone.

He shrugs, “It’s never too late to start.”

Just a few days ago, still somewhat full from some delicious hot lunch only a few hours earlier, I’m working in our cabin when Captain Kalli comes by. Jonathan is presumably hanging off the ship somewhere like a squirrel with his GoPro.

“There’s a special surprise for coffee time today,” he says.

Naturally, I’m delighted at this unexpected news. I love surprises.

“Where is Jonathan? There’s a surprise for him, too,” he continues.

“Oh, I’m sure he’s still on the ship. Hopefully.”

Excited by the prospect of a surprise, I scurry down to the mess room and am met by Jona, the only female crew member. She is holding a plate for me.

A cream puff! Who doesn’t love cream puffs? A cream puff shaped like a…

An chocolate covered penis cream puff.

I burst out laughing. Jona is visibly pleased.

“I made these for you,” she says, proudly. “Here’s one for Jonathan,” she shows me the plate with a pair of beautifully formed, perky breasts.

Jonathan is not yet here, and has no idea that a spectacular set of boobies are waiting for him along with some delicious cocoa.

“You are an artist, Jona.”

I’m about one coconut sprinkled testicle in when Jonathan shows up and receives his plate, somewhat dumbfounded. He clearly wasn’t expecting this either.

“You get the boobs,” I say matter-of-factly in-between a mouth full of balls. There really is no proper etiquette for eating these sorts of things.

I look around and can confirm that everyone else has normal cream puffs. I am at once honored and flattered. After eating the lamb testicles in aspic a few days ago, I feel that this is some sort of reward. We’re officially in now.

Done with my cream puff, and after a few highly inappropriate comments about the pastry that I won’t mention here, I head for the smoking room.

I think I need a cigarette.

Day 6: Gammalsjø

Life on a ship in the open ocean is something special, that much is clear. We are realizing that very few things will have you completely off the grid like this.

We have some access to internet, but besides the brief access to the captain’s PC which he has so generously let us use, we have no wifi, no cell service, no microphones on devices recording conversations, and no credit cards tracking our every move here in the North Atlantic. We are rocked to sleep for 8-10 hours every night, and we have full days of uninterrupted time to focus on our work, something that is completely unheard of if you consider our day jobs where the line between professional and personal life is not just blurred - it is non-existent.

Freedom onboard for me right now is not so much about a feeling of being relieved of obligations on land as much as it is a sense of being completely invisible. The view out my window right now is the bow of the ship in snow and sleet, a few hundred yards of waves beyond that, and then a wall of fog. Thousands of kilometers of nothing are beyond that. We exist as a blue shape on screen on a vessel tracker. A tiny blue dot.

I talked a bit about freedom with Captain Kalli over coffee in the smoking room — about the fact that both Jonathan and I feel as if huge weights have temporarily been lifted off our shoulders. Our minds are free to wander creatively, without constant interruptions and requests. I also ask him if there are a lot of ships on this route, if we will see anyone else on our way east.

“No, we would be surprised to see anyone else out here,” he answers, “we’re alone.”

I let this sink in. It’s thrilling but also a bit unnerving.

“We are finished working,” he continues. “Everyone onboard is just going home now.”

Everyone is still managing their jobs around the ship but there’s a sense of calm in the air — the final course is set for Iceland, no stops in-between, and there’s not much else to do but focus on our work and enjoy the ride until we reach Reykjavik in 4 more days. We discuss the weather conditions over the next week.

I learn about “gammalsjø” — old sea, or old ocean. It’s a type of ocean condition where the air is perfectly serene and calm, but the ocean is rough with leftover storm waves from the past. The waves are not as harsh as powerful as during the storm, the edge is off of them, but they are still there — still big and still rolling around the ocean like a memory.

A friend of mine, Maria Randolph, lost her young niece Danielle in the El Faro disaster last fall. I didn’t know her, but she worked on board as crew. The loss of El Faro was felt strongly in the small communities of midcoast Maine as 3 of the souls onboard the ill-fated ship had connections there. Like gammalsjø, those storm waves are still there, months later, rolling along. Before leaving Portland I asked if I could bring something of Danielle’s along with me on this trip.

Maria graciously gave me a few things to take to sea, including Danielle’s photo and some dried flowers from her memorial. The photo of Danielle, beautiful, bright-eyed, and smiling — with shipping containers behind her — has her own quote on it:

“It’s always hard the first day back but nothing is as awesome as being on a ship…such freedom.”

I pinned the photo up onto the bulletin in our cabin as soon as we came onboard in Portland, but it’s really not until today that I really understood what the quote means. The captain, on one of his visits in the past week, saw the image and I explained the story behind it. He was silent for a moment and then he put it more eloquently than I ever could:

“She is sailing the 8th sea now.”

I will leave the photo hidden on this ship where it won’t be found. I’d like to think that Danielle can keep on sailing for a good while longer, perhaps for many years. When it’s not so rough out and I can go on deck safely, I’ll toss the dried flowers out into the North Atlantic. I will make sure to do it discreetly.

No photos, no video. Invisible.

Such freedom.

Day 7: ICEBERG!

Today, thanks to GPS, satellites, radars, and weather reports, the crew can now tell us when we will get to Iceland, almost within the hour. However, the story goes that when Vikings used to cross the ocean hundreds of years ago, they would have a raven on board.

Scouting ahead into the fog, this raven might bring back a piece of vegetation— a stick, a leaf, or something green from the mainland — to confirm that the ship was close to land. It would be a small thing that would make proximity of solid ground very real. Onboard Selfoss, this green signal is astroturf.

For a good week the TV in the tiny smoking room has shown the Danish signal “Intet Signal” — no signal — on the screen. Today, a soccer game has been showing up sporadically, somewhat pixelated, and flickering in and out. The grass green of the turf looks juicy as hell in the small beige and blue cabin.

“That’s my team, Barcelona,” nods Captain Kalli, as somebody on the team kicks the ball and the signal once again disappears into a flurry of green pixels. The window in the smoking room shows a dense fog surrounding the ship. Selfoss is rolling heavily and she sounds like she is snoring, and each roll is the sound and speed of a deep inhale and exhale. I am convinced that your breathing slows down to follow the ship when you are on board. At this point, both Jonathan and I are used to the massive rolling movement of the ship, and we are making our way around various areas of the ship feeling slightly drunk and not entirely unlike balls in a pinball machine.

Grass green isn’t part of the palette here at all. Life on the ship is mostly beige, blue, orange, yellow, and red.

Any green found on this ship is on the numerous warning signs which function like cryptic menus informing us of all the varieties of ways we can slide into the ocean, lose digits, and puncture eyeballs by accident. I can also count only 2 green containers on deck from the window in our cabin. Other than that, this is a Wes Anderson movie, set in 1980’s primary colors.

The captain tells me that most of the crew will spend a lot of time outdoors, in nature, once off the ship. Soaking up some green as it were.

I’m pretty sure we’ve eaten an entire farm while we’ve been onboard. Sheep, pigs, cows, chickens, ducks have all been on the menu. I suspect that the salami may be horse, but I haven’t asked because it’s so delicious and I’d really rather not know. In any case, I think we’ve run the culinary gamut of any standard farm operation and we still have a few days left in case there’s a goat or a rabbit squirreled away in the galley somewhere. What we haven’t been eating are any greens. Except one.

Iceberg lettuce.

The iceberg lettuce has been showing up, almost apologetically, at various meals on board. It’s difficult to compete with bacon and duck breasts, so I have a lot of empathy for the tired bowl of light green lettuce that everyone ignores. Sometimes the lettuce is alone, sometimes she dresses up with a few cucumber slices and tomatoes, but she isn’t fooling anyone. She is still iceberg lettuce. I always have some, just to be polite.

Over lunch, a crew member asks me how long Jonathan and I will be in Iceland once we arrive. Only a day or two, I answer. He shakes his head.

“It’s not a great time to be in Iceland. It’s just rainy, foggy, and cold.”

“But the nature is still nice,” I say. After all, the story goes that Greenland was named Greenland to attract settlers, and Iceland named Iceland to deter them.

“Yes, the nature is very good,” he concedes.

We’re running out of time on board, so I eat my greens and get back to work.

Day 8: Balance

Just outside Iceland there’s an underwater ledge. The depth of the water goes from 1000 meters to 500 meters very quickly, and with it the waves go from large, deep rolling ones, to shorter, rougher, meaner ones. The closer we get to Iceland, the harder the ship rolls.

This morning, on my way to getting some coffee I came up with a terrific idea for a reality show. It would be called “How Badly Do You Want Your Damn Coffee?” The first episode would feature this ship, and the 5 flights of narrow stairs in the windowless, fireproof hallway that stands between our cabin and the coffee pot. The hallway would function something like a zero gravity wind tunnel and the object of the race would be to get the coffee and return to the room without spilling a drop. Against all odds I’ve become pretty good at this.

Today, while I am sliding around the deck like Bambi in a parka, Jonathan has decided to climb up on the roof of the bridge every two hours today to re-set the battery on his GoPro. I seem to be the only person who thinks this might be a bad idea. Finnur, the 6 foot 3 Viking night watch just shrugs when Jonathan, like some sort of deranged ninja, disappears out the back door of the bridge and skimmies onto the roof in the dark with the wind howling at his back.

“He’s fine,” Finnur says. “There’s a railing.”

I imagine the ship hitting a particularly hard wave and Jonathan getting flicked off the roof into the sea like as if he was a squirrel catapulted off a bird feeder. I decide I simply can’t worry about it, and perhaps there could be a free laptop and his alcohol quota in it for me should the unthinkable happen. I decide to literally just roll with it. Clearly, Jonathan’s balance is just fine.

Something I didn’t account for when planning this trip is my fear of heights and some vertigo. I have enough motion sickness tablets to kill an Icelandic horse, but I forgot that all the ladders and heights might be a problem for me on this ship. Strangely enough, this fear has dissipated somewhat over the last 9 days, maybe because I have had to just deal with it.

A few weeks ago I was at my eye doctor renewing my prescription when I was asked about my vertigo. The doctor told me that his wife had it, and because it basically amounts to some sort of crystals in your ears that are unevenly distributed, her doctor had basically just grabbed her by the head and shaken it. It had, surprisingly, helped a great deal. Perhaps all this getting banged around the last days has cured me of vertigo for good. Rebooting my balance as it were.

Once we disembark it will be a while until the ground doesn’t sway beneath our feet. However, all these days at sea have given us a surprising amount of balance in our lives, and that’s nothing to shake your head at.

Day 9: Ghosts

“The last captain died in bed,” Kalli says, and points to his bedroom. I’m at his desk, posting stuff on social media, clinging to the table as the rolling chair wants to slide across the room at a 20 degree angle.

Jonathan and I have heard some talk about a ghost on board who likes to stay on the bridge. Captain Kalli tells us that he has not seen it, but that a few others claim they have. They think maybe it’s the dead captain.

“Maybe he has unfinished business,” Jonathan says. “Isn’t that what ghosts are? People with unfinished business?”

It seems strangely fitting that a ghost would be traveling with us. The powerful thing about an ocean voyage is not so much about the ship, but the fact that you are not within reach of anyone. You are truly alone and ghostlike on the ocean. We can paint, write, photograph, or watch silly movies in the day room all we like, but if something happens, this is really all you have. This group of people, and this equipment. You can reach out to the whole world online, but you might as well be on the moon if you there’s an emergency. Sure, there are lots of opportunities to feel this way on land as well. but there is something about being on a pitch black ocean with thousands of feet of empty space below that is quite mind boggling if you let your thoughts go there. And if we’re really honest with ourselves, isn’t this voyage just a great, scenic allegory for life in general? For the faint of heart, this thought is quickly quelled by a warm waffle with jam in the mess room.

“Is it safe to burst my appendix now?” I ask, half kidding. The captain has let us know we will likely see land by this evening and we will be arriving in Reykjavik at 7 am tomorrow.

I continue, “I mean, if something like that happened, are any of the crew in a position to perform medical procedures if we weren’t within range of land?”

“I can do a bit of stitching, I suppose,” the captain jokes.

He tells me they have some courses they take to be able to do basic procedures at sea. The thought of having an appendectomy done on the blue leather couch, swabbed with some Johnny Walker from bonded storage is not encouraging. Kalli tells me that the previous cook had heart problems and had requested work on a route where they were always within helicopter range. This is not a typical workplace and accidents do happen. These are not typical office jobs.

Atli works as crew, squeezing in between massive stacks of steel containers on deck, checking numbers, tightening bolts, and generally operating in extremely dicey conditions as his workplace rolls like a damn roller coaster around him. Jonathan has been shadowing him and others with equally crazy jobs mercilessly with his camera, literally getting into every tiny corner of the ship, from inside the cranes 80 feet above the roiling ocean to the rusty bowels of the hull. All accompanied by nothing but ocean in every direction.

“Life is just sacrifice, isn’t it,” Atli says. I’ve caught up with him on a break, and he has a cup of coffee in front of him and some tobacco tucked into his upper lip. His family, including two very young children, live in Norway, and he has a horse farm in Iceland. He has 19 horses, it’s his family’s hobby. His two year old is scared of her horse, but the five year old is warming up to it.

“I can work long shifts here, and because it pays better than most jobs, I can have the horse farm as well. I spend the summer there. It is a sacrifice.”

We couldn’t possibly have more different jobs he and I, but we discuss the similarities of working at sea and of single parenthood — having time off and time on to focus on what’s important in life. How the sacrifice of time to work hard also allows you the life you want when you have time off. Atli’s only regret is that his daughter takes so long to recognize him between his 5 week stints at sea. I tell him about how my son is off with his dad for 3 months on his own ocean voyage and how I worry that our connection will be lost. We are both experiencing periods of being absent from our own lives — somehow living half a life, in order to be more present in the half that matters.

“We are speaking the same language,” he says solemnly before finishing his coffee and leaving to go back into the depths of the ship. I go back to my room to paint.

We could be in Reykjavik now except for our timing. We’re too early get a spot at the dock, so we have to roll around on the ocean a day longer, killing time until there’s space for us. It’s bit like circling an airport waiting to land, that is if your airplane had seats that slid all over the cabin and you peed sideways. We are getting ab workouts trying not to roll out of our bunks. At dinner time I slid a good 6 feet down the galley seated in my chair with a glass of water in one hand and a forkful of spaghetti in the other. It was not very graceful. It’s some sort of fucking miracle that no-one has been stabbed to death accidentally while buttering their toast.

Late that evening when the ship is asleep, Jonathan and I go up to the bridge. A night watch is up there, along with a few others, their faces glowing from the light of the instruments. Maybe the dead captain is here, too, watching from the shadows in the back of the dark room. B.B. King is playing loudly on the stereo, and through the 360 degree views the moon is shining on the black, deadly ocean. Ahead of us is the dark outline of the containers stacked on the deck.

Beyond that is a bright and ghostly green ribbon of Northern Lights, leading the way to shore. ▢